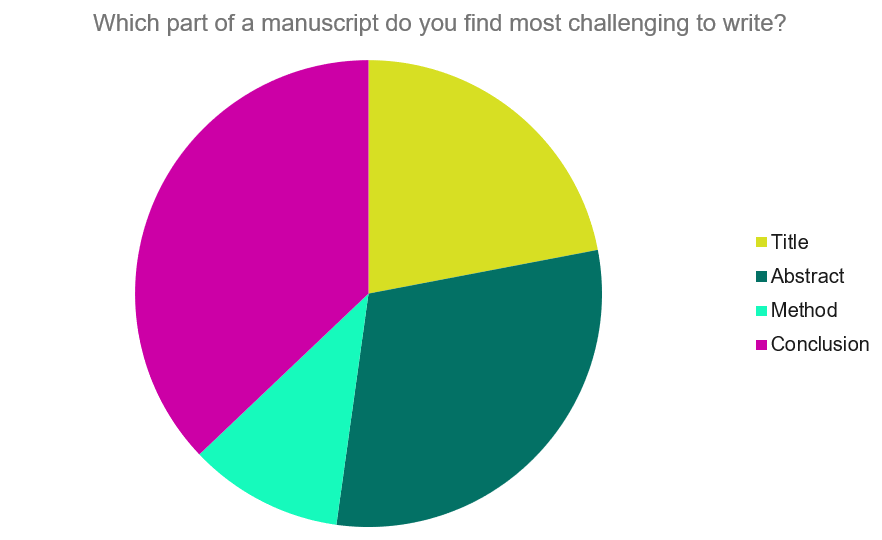

First impressions count — and that’s why the abstract is one of the most important parts of your research paper. Usually between 150-300 words long, the abstract sits at the very beginning of your paper and gives a succinct summary of your research’s aims, methods, and results.

A well-written abstract is crucial to getting your research paper read. “For the vast majority of readers, the paper does not exist beyond its abstract”1: busy researchers will often skim abstracts to check whether the paper is relevant to their own research, and whether it’s worth them reading the full paper. That’s why it’s always worth spending time on your abstract to make sure it’s as impactful as possible. Emerging technologies are helping authors by summarizing their article for them, highlighting the key points and important concepts from the research which can provide a useful starting point for drafting an abstract.

How to Structure your Abstract

Think of your abstract like a film trailer: it’s got to be short, snappy, and give readers an idea of what they can expect.

Although your abstract is the first thing people will see, it’s recommended that it’s the last thing you write. It shouldn’t lift any sections directly from your paper; rather, it should be a completely separate paragraph that’s representative of your research paper as a whole. That means you shouldn’t include any new information that can’t be found within the paper.

If you’re submitting to a journal, they often have their own guidelines for writing abstracts, including structure and a word count. Otherwise, you can follow this quick 4-step guide to help you write a strong and effective abstract.

1. Give Some Context

This first section should be no more than a few sentences. It’s a place for you to succinctly introduce your research and give a little context if needed. Most abstracts use the past tense to talk about previous research, or the present tense if you’re talking about how your research is relevant today.

When writing this section, consider what your purpose was for researching this topic, and explain your goals. For example, is there a problem you want to address, or an emerging trend you wanted to investigate?

The following is an extract from a paper titled ‘How Are Scientists Using Social Media in the Workplace?’2 In just three sentences the author explains the role of social media in society and why their research is relevant:

“Social media has created networked communication channels that facilitate interactions and allow information to proliferate within professional academic communities as well as in informal social circumstances. A significant contemporary discussion in the field of science communication is how scientists are using (or might use) social media to communicate their research. This includes the role of social media in facilitating the exchange of knowledge internally within and among scientific communities, as well as externally for outreach to engage the public.”

2. Describe your Methods

The second part of your abstract should tell the reader what was done, and how. You should generally use the present tense to explain how your study was carried out and, if applicable, give any statistics about your participants.

This section may differ slightly, depending on whether your research paper is scientific or literary. In ‘How Are Scientists Using Social Media in the Workplace?’ the authors go into detail about the sample size and participant backgrounds:

“This study investigates how a surveyed sample of 587 scientists from a variety of academic disciplines, but predominantly the academic life sciences, use social media to communicate internally and externally”

Meanwhile, in the research paper ‘When a Text Is Translated Does the Complexity of Its Vocabulary Change? Translations and Target Readerships’3, the authors place more focus on their technique to analyze the vocabulary of a text:

“We propose a “comparative thermo-linguistic” technique to analyze the vocabulary of a text to determine its academic level and its target readership in any given language. We apply this technique to a large number of books by several authors and examine how the vocabulary of a text changes when it is translated from one language to another.”

3. Summarize your Results

The results section of your abstract is arguably the most important part. Those who read your abstract will primarily want to know about your findings, and so it’s worth spending time making sure this section clearly states the top-level results of your study.

While this section is often the longest part of the abstract, you should try to keep it as brief as possible without going into too much unnecessary detail.

In the abstract for the ‘How Are Scientists Using Social Media in the Workplace?’ paper, the authors use the present tense to explain the key finding of their research:

“Our results demonstrate that while social media usage has yet to be widely adopted, scientists in a variety of disciplines use these platforms to exchange scientific knowledge, generally via either Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, or blogs.”

4. Give a Conclusion

Your conclusion should concisely tie everything together. You might want to touch on the implications of your results in the study field or suggest potential directions for further studies. For example:

“Our data provides a baseline from which to assess future trends in social media use within the science academy.”4

You might even want to highlight any study limitations and how these could be addressed in future — for instance, if your study had a small sample size, you might want to carry out a larger study further down the line.

References

- Andrade, C., 2011. How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(2), p.172.

- Collins, K., Shiffman, D. and Rock, J., 2016. How Are Scientists Using Social Media in the Workplace?. PLOS ONE, 11(10), p.e0162680.

- Rêgo, H., Braunstein, L., D′Agostino, G., Stanley, H. and Miyazima, S., 2014. When a Text Is Translated Does the Complexity of Its Vocabulary Change? Translations and Target Readerships. PLoS ONE, 9(10), p.e110213.

- Collins, K., Shiffman, D. and Rock, J., 2016. How Are Scientists Using Social Media in the Workplace?. PLOS ONE, 11(10), p.e0162680.