Hydroelectric energy, also known as hydroelectricity or hydroelectric power, is a type of energy that uses the power of water in motion — for instance when waterfalls through a reservoir — in order to produce electricity.

Despite its unfamiliar name, however, hydropower is not new technology. In Ancient Egypt, around 300 years BCE, Archimedes’ water screws were used for irrigation. Yet it was not until the 18th century that hydropower was harnessed in order to create electricity. Today, it is widely considered to be the most sustainable form of power generation we have, coming from a renewable energy source without emitting harmful pollutants.

Unfortunately, the big picture is a little more complicated. This article will explain the history and workings of hydroelectric power, and address whether it truly is the cleaner solution for the greener world we’re all hoping for.

Who Discovered Hydroelectric Power?

The modern hydropower turbine emerged from the work of French engineer Bernard Forest de Bélidor,** who wrote the innovative, four-volume book Architecture Hydraulique (1737-1753).

In 1891 however, the Russian-born inventor Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky created the world’s first three-phase electric system. This was an important step in the application of hydropower for generating electricity because now it could be transported across long distances to remote places, while still using similar levels of energy. As XP Power explains, it is a “smoother form of power than single or two-phase systems”, as it enables machines “to run more efficiently, extending their lifetime”.

How Does Hydroelectric Energy Work?

In the words of the Energy Saving Trust: “all streams and rivers flow downhill. Before the water flows down the hill, it has potential energy because of its height”.

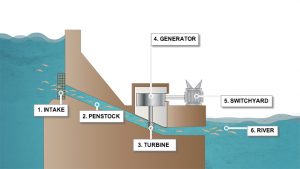

Your standard hydroelectric power plant, therefore, has a reservoir of water, a valve for controlling the amount flowing from it, and an outlet for where this downward flow ends up.

In this way, the water can gain potential energy, stored in its relative position as it travels at an elevated angle before it spills over a dam or hill.

Potential energy converts into kinetic energy as it travels downward. which then turns the blades of a turbine and creates electricity throughout the power plant. Hence, it is one of the oldest forms of renewable energy.

What Are The Types of Hydroelectric Plants?

Not only is it one of the oldest, but hydropower is also one of the most widely-used sources of electricity, making up 16.8% of the world’s total electricity generation.

The most common hydroelectric plant is the impoundment facility — the system described above — which requires a dam to control water flowing from a reservoir and uses gravity to generate potential energy from this downward movement of water.

There are also diversion facilities, which do not use a dam but instead a network of canals to channel the flow toward turbines, which then power electricity generators.

Finally, there is the pumped-storage facility.

In this plant, energy is collected from solar, wind, and nuclear power, and stored by pumping water from a pool that is at a lower elevation uphill, towards a reservoir that is higher up.

When electricity is needed, the water from the reservoir above is released, which travels back down to the lower pool in order to start moving the generator turbine.

Is Hydroelectric Power More Sustainable?

Advantages

Clean and Renewable Energy

Generating electricity through the controlled release of water is less harmful for the environment than coal or natural gas as it does not emit any pollutants.

While finite resources are nonetheless necessary to build hydropower systems and plants, once they are up and running these can operate without the need to burn any coal, shale, natural gas or any other form of fossil fuel.

The water they use is completely recycled, meaning that hydropower is a sustainable way to produce electricity, provided that no irreparable changes happen to the water cycle in the short and long term.

Compatibility

Most hydroelectric plants are storage or pumped storage facilities that can keep great quantities of water in pools or reservoirs.

This means that 99.9% of the time, they will have water stored that they can use to then produce hydroelectric power from, making these plants a stable source of energy that can be drawn on demand.

Wind and solar power, on the other hand, rely on the fickle behaviour of their respective elements.

We are able to therefore use hydropower in tandem with wind and solar, providing a compatible and practical form of renewable energy.

Disadvantages

Expense

As we touched on earlier, not only does constructing a hydropower plant consume finite resources, it is an expensive enterprise.

Reservoirs, dams, and turbines that can generate power demand a large investment, and though this produces a more cost-effective energy solution, in the long run, upfront it is costly.

There is also the factor of dwindling space available for building hydroelectric plants, making land more scarce and consequently more expensive.

Environmental impact

Though renewable, it’s important not to understate that hydropower plants do have an environmental effect.

Predominantly, storage hydropower or pumped storage hydropower systems impact the natural flow of a river system, affecting the quality of water, and displacing animals and even humans.

While these vary in terms of overall impact depending on where the plant is, most plants use storage or pumped storage systems that disrupt the flow of river water.

They can also raise the temperature of the water, and produce sediment that affects wildlife like birds and fish.

Can we Make Hydropower Even More Sustainable?

The International Hydropower Association (IHA) recently made the case at COP26 that “the only proven decarbonized renewable technology able to support solar and wind at scale is hydropower”.

While the benefits of energy generated with limited carbon emissions is hard to argue with, more needs to be done before the IHA can safely call this form of power fully sustainable.

One such example of how to alleviate the ecological disruption caused by hydroelectric plants can be found in the Restoration Hydro projects.

These are specifically designed to deflect, rather than injure, any fish that come into contact with the turbines.

It bodes well, then, that the IHA recognises solutions like these, and has proposed a series of tools and guidelines for implementing sustainable practices in modern hydropower. Only time can tell us if these will be sufficient.